The radical moral implications of luck in human life

Acknowledging the role of luck is the secular equivalent of religious awakening.

By

Around the same time, there was another minor uproar when Refinery29 published “A Week in New York City on $25/Hour,” an online diary by someone whose rent and bills are paid for by her parents. It turns out $25 an hour goes a lot further if you have no expenses!

These episodes illustrate what seems to be one of the enduring themes of our age: socially dominant groups, recipients of myriad unearned advantages, willfully refusing to acknowledge them, despite persistent efforts from socially disadvantaged groups. This is not a new theme, of course — it waxes and wanes with circumstance — but after a multi-decade rise in inequality, it has come roaring back to the fore.

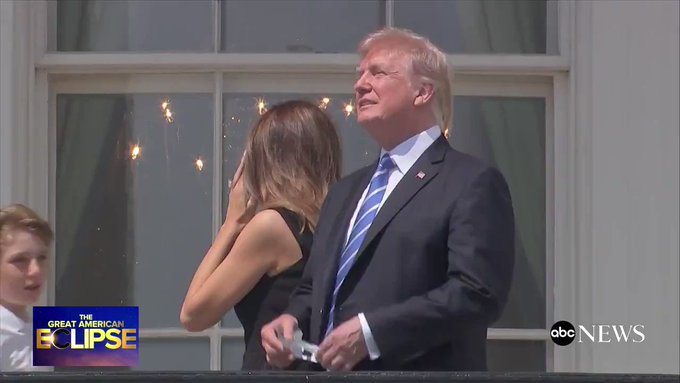

Of course, socially dominant groups have every incentive to ignore luck. And they have found a patron saint in President Trump, who once claimed, “My father gave me a very small loan in 1975, and I built it into a company that’s worth many, many billions of dollars.”

Neither side of that claim is true. But in this, as in so much else, Trump’s brazenness serves as cover, a signal that it’s still okay to cling to this myth.

These recent controversies reminded me of the fuss around a book that came out a few years ago: Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy, by economist Robert Frank. (Vox’s Sean Illing interviewed Frank last year.) It argued that luck plays a large role in every human success and failure, which ought to be a rather banal and uncontroversial point, but the reaction of many commentators was gobsmacked outrage. On Fox Business, Stuart Varney sputtered at Frank: “Do you know how insulting that was, when I read that?”

It’s not difficult to see why many people take offense when reminded of their luck, especially those who have received the most. Allowing for luck can dent our self-conception. It can diminish our sense of control. It opens up all kinds of uncomfortable questions about obligations to other, less fortunate people.

Nonetheless, this is a battle that cannot be bypassed. There can be no ceasefire. Individually, coming to terms with luck is the secular equivalent of religious awakening, the first step in building any coherent universalist moral perspective. Socially, acknowledging the role of luck lays a moral foundation for humane economic, housing, and carceral policy.

Building a more compassionate society means reminding ourselves of luck, and of the gratitude and obligations it entails, against inevitable resistance.

So here’s a reminder.

How much credit do we deserve for who, and where, we end up?

How much moral credit are we due for where we end up in life, and for who we end up?Conversely, how much responsibility or blame do we deserve? I don’t just mean Kylie Jenner or Donald Trump — all of us. Anyone.

How you answer these questions reveals a great deal about your moral worldview. To a first approximation, the more credit/responsibility you believe we are due, the more you will be inclined to accept default (often cruel and inequitable) social and economic outcomes. People basically get what they deserve.

The less credit/responsibility you believe we are due, the more you believe our trajectories are shaped by forces outside our control (and sheer chance), the more compassionate you will be toward failure and the more you will expect back from the fortunate. When luck is recognized, softening its harsh effects becomes the basic moral project.

Understanding the role of luck begins with getting past the old “nature versus nurture” debate, which has always captivated the public, not so much because of the science but because of the deeper existential questions involved.

“Nature” has come to serve roughly as code for the stuff we’re stuck with, our bodies, our genes — an arrow fate has already fired, with a preset path. And “nurture” has become shorthand for our capacity for change, our ability to be shaped by circumstances, other people, and ourselves, to wiggle and move about within that path, or even escape it. It’s shorthand for our range of control over our fates.

But this has always struck me as a misguided way to look at it.

Both nature and nurture happen to you

Of course it is true that you have no choice when it comes to your genes, your hair color, your basic body shape and appearance, your vulnerability to certain diseases. You’re stuck with what nature gives you — and it does not distribute its blessings equitably or according to merit.

But you also have no choice when it comes to the vast bulk of the nurture that matters.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12323139/nurture_secondary.jpg)

Child development psychologists tell us that deep and lasting shaping of neural pathways happens in the first hours, days, months, and years of life. Basic dispositions are formed that can last a lifetime. Whether you are held, spoken to, fed, made to feel safe and cared for — you have no choice in any of it, but it more or less forms your emotional skeleton. It determines how sensitive you are to threat, how open you are to new experience, your capacity to exercise empathy.

Children aren’t responsible for how they spend their formative years and the permanent imprint it makes upon them. But they’re stuck with it.

Legally speaking, here in the US, we don’t consider people autonomous moral agents, responsible for their own decisions, until they are 18. Obviously, different cultures have different ages and markers for adulthood (moral agenthood), but all cultures mark a transition. At some point, a child, an instinctual creature not fully responsible for their decisions, becomes an adult, capable of using higher cognitive functions to shape and moderate their behavior according to shared standards, and to be held accountable if they don’t.

For the purposes of this argument, it doesn’t matter much where you draw the line between child and adult. What matters is that it takes place after the bulk of temperament, personality, and socioeconomic circumstance are in place.

So, then, here you are. You turn 18. You are no longer a child; you are an adult, a moral agent, responsible for who you are and what you do.

By that time, your inheritance is enormous. You’ve not only been granted a genetic makeup, an ethnicity and appearance, by accidents of nature and parentage. You’ve also had your latent genetic traits “activated” in a very specific way through a specific upbringing, in a specific environment, with a specific set of experiences.

Your basic mental and emotional wiring is in place; you have certain instincts, predilections, fears, and cravings. You have a certain amount of money, certain social connections and opportunities, a certain family lineage. You’ve had a certain amount and quality of education. You’re a certain kind of person.

You are not responsible for any of that stuff; you weren’t yet capable of being responsible. You were just a kid (or worse, a teen). You didn’t choose your genes or your experiences. Both nature and the vast bulk of the nurture that matters happened to you.

And yet when you turn 18, it’s all yours — the whole inheritance, warts and all. By the time you are an autonomous, responsible moral agent, you have effectively been fired out of a cannon, on a particular trajectory. You wake up, morally speaking, midflight.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12323439/cannon2.gif)

Bettering ourselves frequently means overcoming our own inheritances

How capable are we altering our trajectories? How much can we change ourselves?

Here, a distinction made famous by psychologist Daniel Kahneman in his seminal Thinking, Fast and Slow is helpful. Kahneman argues that humans have two modes of thinking: “system one,” which is fast, instinctual, automatic, and often unconscious, and “system two,” which is slower, more deliberative, and emotionally “cooler” (generally traced to the prefrontal cortex).

Our system one reactions are largely hardwired by the time we become adults. But what about system two?

We do seem to have some control over it. We can use it, to some extent, to shape, channel, or even change our system one reactions over time — to change ourselves.

Everyone is familiar with that struggle; indeed, the battle between systems one and two tends to be the central drama in most human lives. When we step back and reflect, we know we need to exercise more and eat less, to be more generous and less grumpy, to manage time better and be more productive. System two recognizes those as the right decisions; they make sense; the numbers work out.

But then the moment comes and we’re sitting on the couch and system one feels very strongly that it doesn’t want to put on running shoes. It wants greasy takeout food. It wants to snap at the delivery guy for being late. Where is system two when it’s needed? It shows up later, full of regret and self-recrimination. Thanks a lot, system two.

To become a better person is, at least to some degree, to consciously decide what kind of person one wants to be, what kind of life one wants to lead, and to enforce that meta-decision through day-to-day smaller decisions. They say you are what you do repeatedly; our choices become habit and habit becomes character. So forming a good character, becoming a good person, means repeatedly choosing to do the right thing until it becomes habit.

To make this more concrete, an example: For whatever reason, I hate waiting on people. I can barely stand to walk behind people on the sidewalk. Driving behind people leaves me in constant, low-level seething rage. Watching the people ahead of me in line at the store bumble through their slow transactions makes me want to claw my eyes out.

When I use system-two thinking, I understand that this instinctual reaction of mine is both irrational and uncharitable — irrational because we’re all always waiting for one another and there’s no way to avoid it; uncharitable because I expect alacrity from others than I don’t always display myself. I make others wait just as much or more than anyone, but I absolutely can’t wait for others.

To put it more bluntly, I tend to be kind of an asshole in that particular way. And I don’t want to be! It makes other people tense. It makes me miserable. It serves absolutely no purpose.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12323231/roadrage_secondary.jpg)

The only way to change it is to use system-two thinking to override system one — to intervene in my own anger — again and again, until a different, better reaction becomes habitual and I become, in a literal sense, a different, better person. (That project is, uh, ongoing.)

The same is true for being a good parent, saving money, making more friends, or any other long-term life goal; it often involves overriding our own instincts — many of which are grossly maladaptive.

Do people deserve moral credit for what they do with their system-two thinking? Perhaps that’s the mechanism through which meritocracy works, through which people really do get what they deserve?

If you are a go-getter, lucky for you! No, really — that’s luck too.

There are two reasons why system-two thinking can’t get us out of the luck trap: Both the capacity and the need for system-two thinking are inequitably distributed.

First, the capacity.

Using system two to regulate system one is difficult. Exercising the kind of self-discipline necessary to override system one reactions with deliberative, system-two choices is effortful. It drains energy. (See Brian Resnick’s fascinating discussion of the famous “marshmallow test” for more on this.)

Doing it requires certain conditions: a degree of self-possession, a degree of freedom from more basic physical needs like food and shelter, some training and habituation. Even with those advantages, it’s difficult. There’s an entire “life hacking” genre devoted to tricks and techniques that system-two thinking can use to counteract system one’s predilections for salty snacks and procrastination.

And the thing is, not everyone has equal access to those conditions. Whether and how much you have the ability to exercise system two in this way is largely — you guessed it — part of your inheritance. It too depends on where you were born, how you were raised, the resources to which you had access.

Even our desire and ability to alter our trajectory is largely determined by our trajectory.

Second, the need.

Some people don’t much need the ability to self-regulate, because their failures of self-regulation are forgiven and forgotten. If you are, say, a white male born to wealth, like Donald Trump, you can blunder about and fuck up over and over again. You’ll always have access to more money and social connections; the justice system will always go easy on you; you’ll always get more second chances. You could even be president someday, without being required to learn anything or develop any skills relevant to the job.

But if you are, say, a black male, you are called upon to exercise an extraordinary degree of self-regulation. You will frequently be surrounded by people on a hair trigger, prone to suspect or fear you, to turn down your rental application or deny you a loan or pass you over for a “safer” job applicant, prone to calling the cops on you, prone, if they are cops, to target and abuse you.

And, especially if you are poor, one step out of line — one incident at school, one brush with the justice system, one stupid teenage prank — can mean years or even a lifetime of consequences. Subaltern groups have to self-regulate twice as much to have half a chance.

Neither the capacity nor the need for self-regulation is distributed evenly or fairly. In a dark irony, we demand much more of it from those — the poor, the hungry, the homeless or housing-insecure — likely to have the least access to the conditions that make it possible. (Just one more way it’s expensive to be poor.)

Your capacity for self-regulation and self-improvement, and your need for them, are both part of your inheritance. They come to you via life’s lottery. Via luck.

Acknowledging luck is profoundly threatening to the lucky

I get why people bridle at this point. They want credit for their achievements and for their better qualities. As Varney said, it can be insulting to be told that one’s success is in large part a lucky roll of the dice.

Of course, people aren’t nearly as eager to take credit for their failures and flaws. Psychologists have shown that all humans are subject to “fundamental attribution error.” When we assess others, we tend to attribute successes to circumstance and failures to character — and when we assess our own lives, it is the opposite. Everyone’s relationship with luck is somewhat self-interested and opportunistic.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12323171/such_is_life_secondary.jpg)

And the more one benefits from life’s lottery, the greater the incentives to deny it. As a class, the lucky have every political incentive to frame social and economic outcomes as reflective of a natural order. Life’s winners have been telling stories about why they’re special since civilization began.

But that’s my point about the moral implications of luck: They are radical and inevitably corrosive to the established order. They cast doubt on every form of privilege and light on every mechanism by which privilege perpetuates itself.

Acknowledging luck — or, more broadly, the pervasive influence on our lives of factors we did not choose and for which we deserve no credit or blame — does not mean denying all agency. It doesn’t mean people are nothing more than the sum of their inheritances, or that merit has no role in outcomes. It doesn’t mean people shouldn’t be held responsible for bad things they do or rewarded for good things. Nor does it necessarily mean going full socialist. These are all familiar straw men in this debate.

No, it just means that no one “deserves” hunger, homelessness, ill health, or subjugation — and ultimately, no one “deserves” giant fortunes either. All such outcomes involve a large portion of luck.

The promise of great financial reward spurs risk-taking, market competition, and innovation. Markets, properly regulated, are a socially healthy form of gambling. There’s no reason to try to completely equalize market outcomes. But there’s also no reason to allow hunger, homelessness, ill health, or subjugation.

And there’s no reason we shouldn’t ask everyone, especially those who have benefited most from luck — from being born a certain place, a certain color, to certain people in a certain economic bracket, sent to certain schools, introduced to certain people — to chip in to help those upon whom life’s lottery bestowed fewer gifts.

And it is entirely possible to do both, to harness market competition while using the wealth it generates to raise up the unlucky and give them greater access to that very competition.

“If you want meritocracy,” Chris Hayes argued in his seminal book Twilight of the Elites, “work for equality. Because it is only in a society which values equality of actual outcomes, one that promotes the commonweal and social solidarity, that equal opportunity and earned mobility can flourish.”

Or as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the democratic socialist firebrand who won her House Democratic primary in New York’s 14th District, is fond of saying, “in a modern, moral, and wealthy society, no person should be too poor to live.”

Neither human genes nor human societies distribute life’s gifts according to any principle we would recognize as fair or humane, given the extraordinary role of luck in our lives. We all become adults with wildly different inheritances, starting our lives in radically different places, propelled toward dramatically different destinations.

We cannot eliminate luck, nor achieve total equality, but it is easily within our grasp to soften luck’s harsher effects, to ensure that no one falls too far, that everyone has access to a life of dignity. Before that can happen, though, we must look luck square in the face.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/60963669/lead_art_draft.0.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment