The Black-White Divide in Suspensions: What Is the Role of Family?

Strong Families.

Sustainable Societies.

The Institute for Family Studies (IFS) is dedicated to strengthening marriage and family life, and advancing the well-being of children through research and public education. Addressing family life is what we do, and we invite you to learn more about ways to strengthen families in America and around the world.

Black students are more likely to get in trouble in school and to end up suspended, compared to white students. This racial disparity in school discipline is both a cause and consequence of enduring racial inequality in America. And it is important because it means that black students, especially black boys, are more likely to end up on the wrong track: getting less schooling, heading towards trouble with the criminal justice system, and, later in life, having fewer opportunities in the labor force.1 What has been called the “school-to-prison pipeline” often starts in the principal’s office and ends in prison, with school suspensions increasing the risk that black boys, in particular, end up incarcerated.2

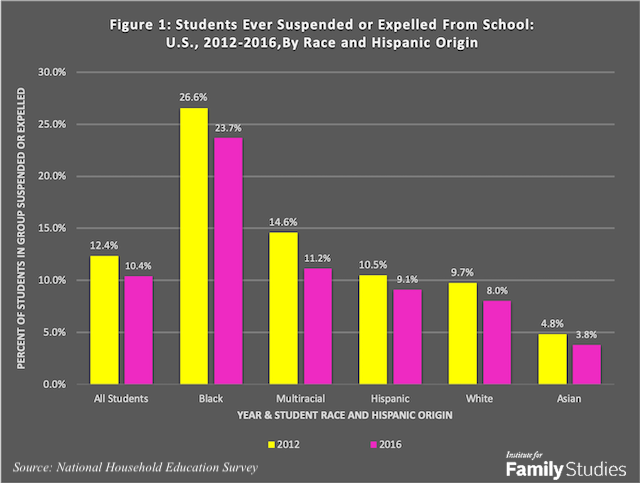

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has recently spotlighted racial and ethnic disparities in school disciplinary actions, such as being suspended or expelled from school.3 Figure 1 illustrates this racial inequality, showing that in 2016 nearly 24% of black students in U.S. elementary and secondary schools had been suspended at least once, as our new analysis of the National Household Education Survey (NHES) shows.4 By contrast, only a third as many white students (8%) and one-sixth as many Asian students (4%) had been suspended. There was a slight but significant reduction in the overall frequency of suspensions between 2012 and 2016, as Figure 1 indicates, but large differences across racial groups remained.5

We do not doubt that racial variation in suspensions is partly a consequence of racial prejudice or “implicit bias” on the part of teachers and school administrators. Black students, especially black boys, are more likely to be surveilled and punished for their behavior, even when that behavior is similar to that of white peers who are not disciplined.6 There is also evidence that the racial composition of teachers in schools shapes patterns of school discipline for African American students.7

But there are legitimate reasons for believing that some of the racial differences in school suspensions and discipline are based upon real, not just perceived, differences in students’ behavior.8 We focus here on the possibility that some of these differences are related to family factors, including notable differences in family structure by race. Students who come from chaotic homes, single-parent families, or non-intact families are less likely to get the consistent attention, affection, and discipline they need to flourish and develop self control. Their families typically have less money, which affects the quality of their neighborhoods and their neighborhood peers, which is also an important influence on school conduct. And they are also more likely to be exposed to conflict, stress, frequent moves, and neglect—all risk factors for delinquent and disruptive behavior.9 Indeed, our data indicate that rates of school contact for student misbehavior are nearly twice as high among students living with separated or divorced parents as among those living with stably married parents. And they are higher still among students who live apart from both biological parents, being cared for instead by grandparents or foster parents.10

Comments

Post a Comment